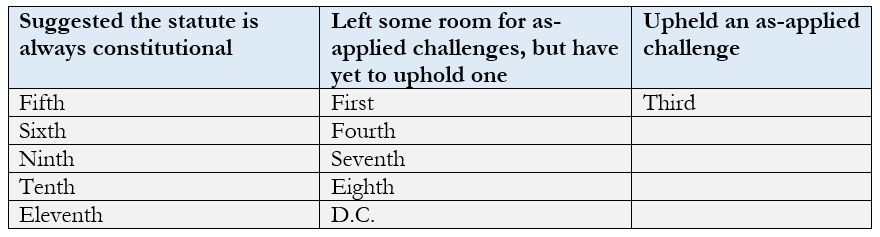

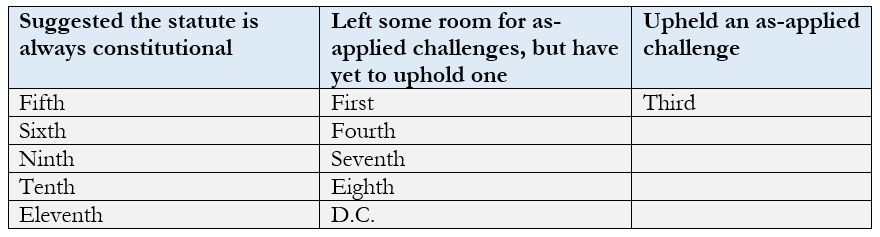

In Kanter v. Barr, decided this March, the Seventh Circuit rejected a non-violent felon’s as-applied challenge to 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(1), which prohibits those convicted of (nearly) all felony offenses from possessing firearms for life. The majority decision, and the dissent, highlight a fraught debate about the historical justification undergirding these types of prohibitions. All circuits have rejected facial challenges to the federal law, but there is some division about whether and how as-applied challenges can succeed:

In the Kanter case, Rickey Kanter previously owned a business that made therapeutic shoes for diabetics and individuals with serious foot disease. He lied about the physical specifications of the shoes, claiming they met federal requirements when they did not, and was later convicted of mail fraud for bilking Medicare out of hundreds of thousands of dollars. That conviction rendered him incapable of owning a gun. He argued that because his conviction was not for a crime of violence, applying the firearm prohibition to him violated his Second Amendment rights.

The Third Circuit’s 2016 en banc ruling in Binderup—which produced no majority opinion—demonstrated the disagreement about the rationale for felon dispossession laws. That debate, which Kanter reignites, is whether the prohibition is justified by the individual’s perceived (1) lack of virtue or (2) propensity for violence. The rationale matters because it typically informs the first step of how courts consider Second Amendment challenges: does the conduct or person at issue fall within the scope of the Second Amendment’s protection? If virtue is the touchstone, then courts are more likely to consider felons as a class unprotected by the Amendment. But, as the Seventh Circuit majority (Judges Flaum and Ripple) says, “[i]f the founders were really just concerned about dangerousness, not a lack of virtue, nonviolent felons like Kanter arguably fall within the scope of the Second Amendment’s protections.” The Seventh Circuit majority, not wanting to wade into the debate over whether the felon prohibition was justified by considerations of virtue vs. danger, instead assumed that Kanter fell within the Second Amendment’s protection and moved to step two of the analysis: whether the law is appropriately tailored to an important enough government interest. The court ultimately upheld the law under intermediate scrutiny.

In a lengthy dissent, Judge Amy Coney Barrett sought to clarify a “conceptual point” about the coverage question. Here, she quibbled not so much with the majority (which had assumed coverage) as with approaches by other judges, including those in Binderup, who see the virtue vs. danger question as a threshold question of whether the Second Amendment even covers a particular person. She highlights the two views:

Some maintain that there are certain groups of people—for example, violent felons—who fall entirely outside the Second Amendment’s scope. . . . Others maintain that all people have the right to keep and bear arms but that history and tradition support Congress’s power to strip certain groups of that right.

In other words, the conceptual question is whether a certain class of persons simply has no Second Amendment rights at all or has such rights but can be permissibly stripped of them. I think of this distinction as similar to that between void vs. voidable contracts. Judge Barrett opts for the voidable view; a felon is protected by the Second Amendment unless and until the legislature strips her of that right. Or, as she puts it, “a person convicted of a qualifying crime does not automatically lose his right to keep and bear arms but instead becomes eligible to lose it.” On her view, then, there’s no first step when dealing with persons. They all fall within the protection of the Second Amendment and the only question is whether the government may permissibly take away their right. After surveying the historical arguments for doing so, Judge Barrett concludes that the government can only permissibly take away the rights of those felons who are dangerous. Because the government provided no evidence that Kanter was himself dangerous, or that mail fraudsters as a class are dangerous, the application of § 922(g)(1) to him violated the Second Amendment.

With the Supreme Court showing perhaps slightly more willingness to entertain Second Amendment challenges, the Seventh Circuit’s decision might not be the last word on whether Rickey Kanter can own a gun. (See also Kevin Marshall’s interesting piece, “Why Can’t Martha Stewart Have a Gun?”) Indeed, if the Supreme Court adopts an altogether new framework in the upcoming New York State Rifle & Pistol Association case, then the rationale question that the Kanter majority sidesteps, and the dissent takes on, may make all the difference in the world.