The June 19, 1861, editorial in the Charleston Mercury newspaper warned: “War is bloody reality, not butterfly sporting. The sooner men understand this the better.” During the four-year course of the Civil War, the entire country—North and South—would come to the same grim realization. There were seemingly endless lists of thousands of soldiers killed or wounded in battle or dead of disease. Thousands more, both Union and Confederate, languished in prisoner of war camps, enduring hardships that previously it had been inconceivable for civilized people to inflict upon one another.

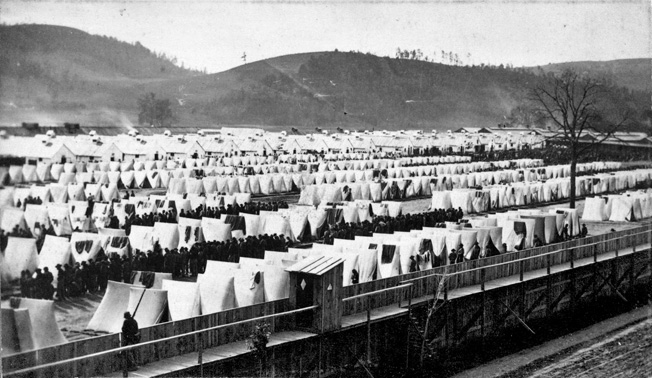

From 1861 to 1865, more than 150 prison camps were established by the Union and Confederate governments. Estimates of the total numbers of prisoners taken and deaths that occurred in captivity vary widely, and Confederate records are incomplete. However, the Official Records of the war cites a total of 347,000 men—220,000 Confederate and 127,000 Union—who endured the privations of being prisoners of war. These privations ranged from inadequate shelter and clothing, poor hygiene, and the monotonous passage of time to outright starvation, intentional cruelty, harsh summary justice, swarming vermin, and rampaging disease. More than 49,000 prisoners died in captivity, at least 26,440 Confederate and 22,580 Union, an overall mortality rate of 14 percent. Twelve percent of Confederate prisoners and 18 percent of Union captives never returned from incarceration.

As in all wars, the victors tend to write the history, and Confederate prisons have become notorious for a litany of horrors. But the simple truth is that neither side could fully claim the moral high ground. Neither side was prepared to accommodate the large numbers of prisoners taken during the war, which many believed would be of short duration but which dragged on for four years of incredible misery.

From the outset, the South suffered shortages of basic commodities such as medicines, foodstuffs, and textiles due to the strangling Union blockade that stretched from the major ports of the mid-Atlantic to the Gulf coast of Texas. The war on land was fought largely in the South, soaking rich farmland with blood. Thousands of Southern farmers left home to serve in the Confederate Army, and few able-bodied men remained behind to tend whatever crops could be produced in straitened circumstances.

With threadbare Confederate soldiers serving in the field without shoes, subsisting on a handful of cornmeal or a few peanuts, the Southern government faced a virtually insurmountable task to provide adequately for thousands of Union prisoners. Nevertheless, early in the war the Confederate Congress resolved that the rations furnished prisoners of war “shall be the same in quantity and quality as those furnished to enlisted men in the army of the Confederacy.” It sounded good on paper.

In the North, more plentiful food supplies, the availability of medical care, and the relative abundance of resources should have weighed positively on the treatment of prisoners. In too many instances, however, conditions were scarcely better than the worst of the prisons in the South. Administrative indifference, ineptitude, and corruption combined with a desire to mete out the same treatment to Confederate prisoners that was rumored to exist in Southern prisons. Camp Douglas in Chicago and Elmira in upstate New York—prosperous communities both—left horrible legacies of their own.

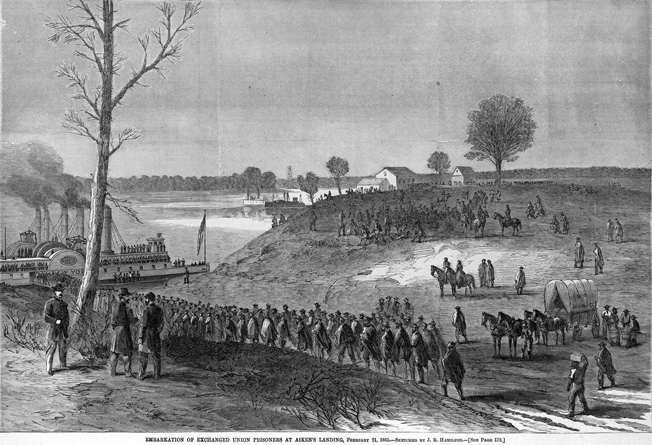

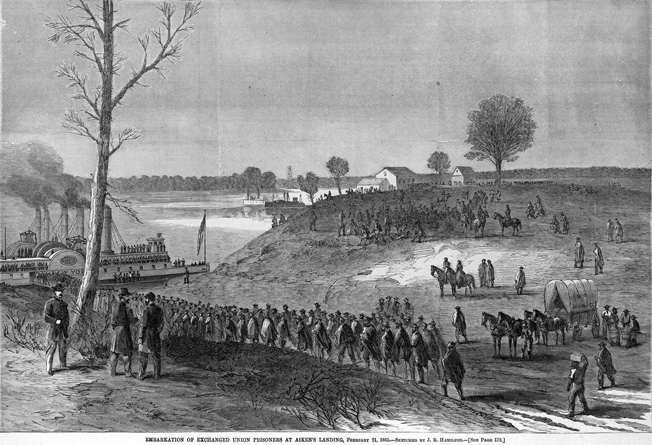

The burden of feeding and sheltering prisoners steadily increased as the war progressed. Early in the conflict, a system of parole and exchange was utilized extensively, and thousands of soldiers were returned to their units. Patterned after a similar system that had seen widespread use in Europe, officers of equal rank were exchanged one for another, while enlisted men were exchanged on a number-by-number basis. When an even exchange was not immediately possible, officers were exchanged for a certain number of enlisted men, such as one captain for six enlisted soldiers. Parole was sometimes extended to prisoners when a timely exchange was not expected. Parole often took place within 10 days of capture, and the system worked reasonably well for a while as prisoners were returned to their respective sides and rejoined the ranks when notified that a proper exchange had occurred. At times parolees went home to await the official exchange; however, these individuals were often reluctant to return to service. Therefore, paroled prisoners were frequently kept near their units until word of an exchange was received.

Over time, the system became increasingly untenable due to the sheer weight of numbers. With the surrender of Fort Donelson, Tennessee, in February 1862, nearly 12,400 Confederate prisoners were captured by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Union forces. The Confederate commander at Fort Donelson, Maj. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, a personal friend of Grant’s, was imprisoned in Boston until he was exchanged. Another 7,000 captured soldiers were sent to the infamous Camp Douglas; the rest were scattered throughout other prisons in the North.

On July 22, 1862, the Confederate and Union governments agreed to a formalized program of exchange known as the Dix-Hill Cartel, named for its principal negotiators, Union Maj. Gen. John A. Dix and Confederate Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill. Prior attempts to formalize exchange protocol had been complicated by several factors. Since the North viewed the conflict as a civil insurrection rather than a war between two sovereign nations, Abraham Lincoln wanted to avoid any action that might legitimize the Confederate government. A formal agreement to exchange prisoners, in the eyes of many observers, particularly those in foreign governments, might do just that.

Fragile from the beginning, the Dix-Hill Cartel survived with limited interruption for only five months. On December 28, 1862, U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton suspended the exchange of commissioned officers in response to a proclamation by Confederate President Jefferson Davis that labeled Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, commander of the forces occupying New Orleans, “a felon deserving of capital punishment.” The Davis proclamation followed Butler’s execution of William B. Mumford, a civilian resident of New Orleans who reportedly had pulled down the U.S. flag that had been raised above the city’s former mint and torn the banner to shreds. A harmless act of vandalism was raised to a fatal act of treason.

By the spring of 1863, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, general-in-chief of the Union Armies, halted all major exchanges. This action was in response to Confederate assertions that Southern soldiers captured by Grant at Vicksburg and subsequently paroled would be considered unilaterally exchanged. A May 1, 1863, joint resolution of the Confederate Congress rendered the decision to continue the exchange program absurd. The resolution asserted that captured African American soldiers who had once been slaves would be treated as runaways rather than soldiers and would be returned to their former owners if possible. It further threatened that “every white person being a commissioned officer who shall command Negroes or mulattoes in arms against the Confederate States shall be deemed as inciting servile insurrection, and shall if captured be put to death or be otherwise punished at the discretion of the Court.”

By then, the protracted war had significantly drained Southern manpower, and the exchange of prisoners was the primary method by which the Confederates replenished the depleted ranks of their field armies. An effort to revive a formal exchange system fell apart after representatives of the U.S. government refused to receive Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens in Washington, D.C., under a flag of truce. Sporadic prisoner exchanges did continue as Butler negotiated with the Confederates under the watchful eye of Secretary Stanton. Butler and Confederate exchange agent Robert Ould arranged the transfer of large numbers of prisoners in the autumn of 1864, particularly those who had been held for the longest time or were in poor health and deemed unfit for further duty. Significant exchanges took place at Savannah and Charleston.

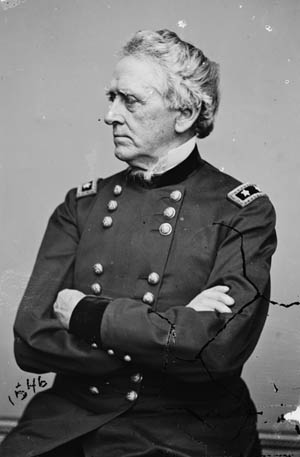

The relentless Grant recognized the fact that continued prisoner exchanges would actually prolong the war. Grant believed that the South could be subdued most efficiently through attrition, as evidenced by his continuation of the Army of the Potomac’s offensive in Virginia in the spring of 1864 despite horrendous casualties. In April of that year, Grant halted exchanges on the basis of the Vicksburg disagreement and the proposed mistreatment of black prisoners by the Confederates. Grant stated his pragmatic perspective in an August 18, 1864, dispatch to Butler, noting: “It is hard on our men held in Southern prisons not to exchange them, but it is humanity to those left in the ranks to fight our battles. Every man released on parole or otherwise becomes an active soldier against us at once, either directly or indirectly. If we commence a system of exchange which liberates all prisoners taken, we will have to fight on until the whole South is exterminated.”

Although Lincoln had hesitated to authorize exchanges during the first year of the war, he had bowed to political pressure and to the rising concern of family members whose loved ones were held in Confederate prisons and allowed the Dix-Hill Cartel to become operative. Now he remained notably quiet on the topic, leaving it to Grant to publicly state that future prisoner exchanges would be suspended due to the exigencies of war.

While politicians and high-ranking military commanders debated, prisoners on both sides suffered. Escape attempts occurred with regularity and were infrequently successful. Confederate Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan and a few of his daredevil cavalrymen tunneled their way to freedom from the Ohio State Penitentiary. The largest escape of the war took place at Libby Prison in the Confederate capital of Richmond when more than 100 Union officers broke out on February 9, 1864, and 59 of them managed to elude recapture.

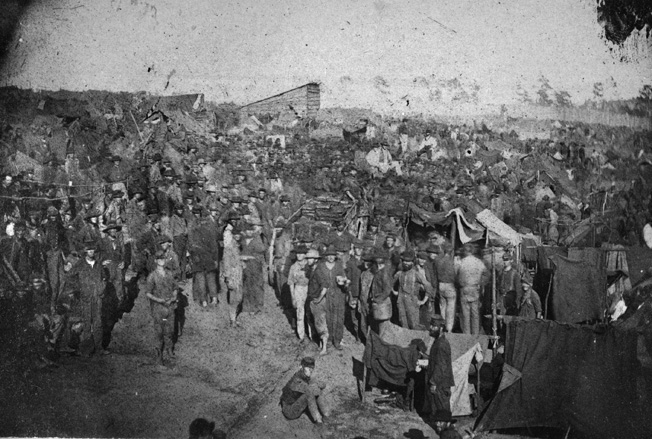

Within three months of Grant’s suspension order in April 1864, the population of Andersonville prison had grown to more than 20,000, twice its original capacity. At its peak in August, the stockade housed over 33,000 Union soldiers in utter squalor. In July 1864, then-Captain Henry Wirz paroled several Andersonville prisoners, who carried a petition to Washington, D.C., begging for the reinstatement of large-scale prisoner exchanges. Lincoln declined to meet with them, and no action was taken on their plea.

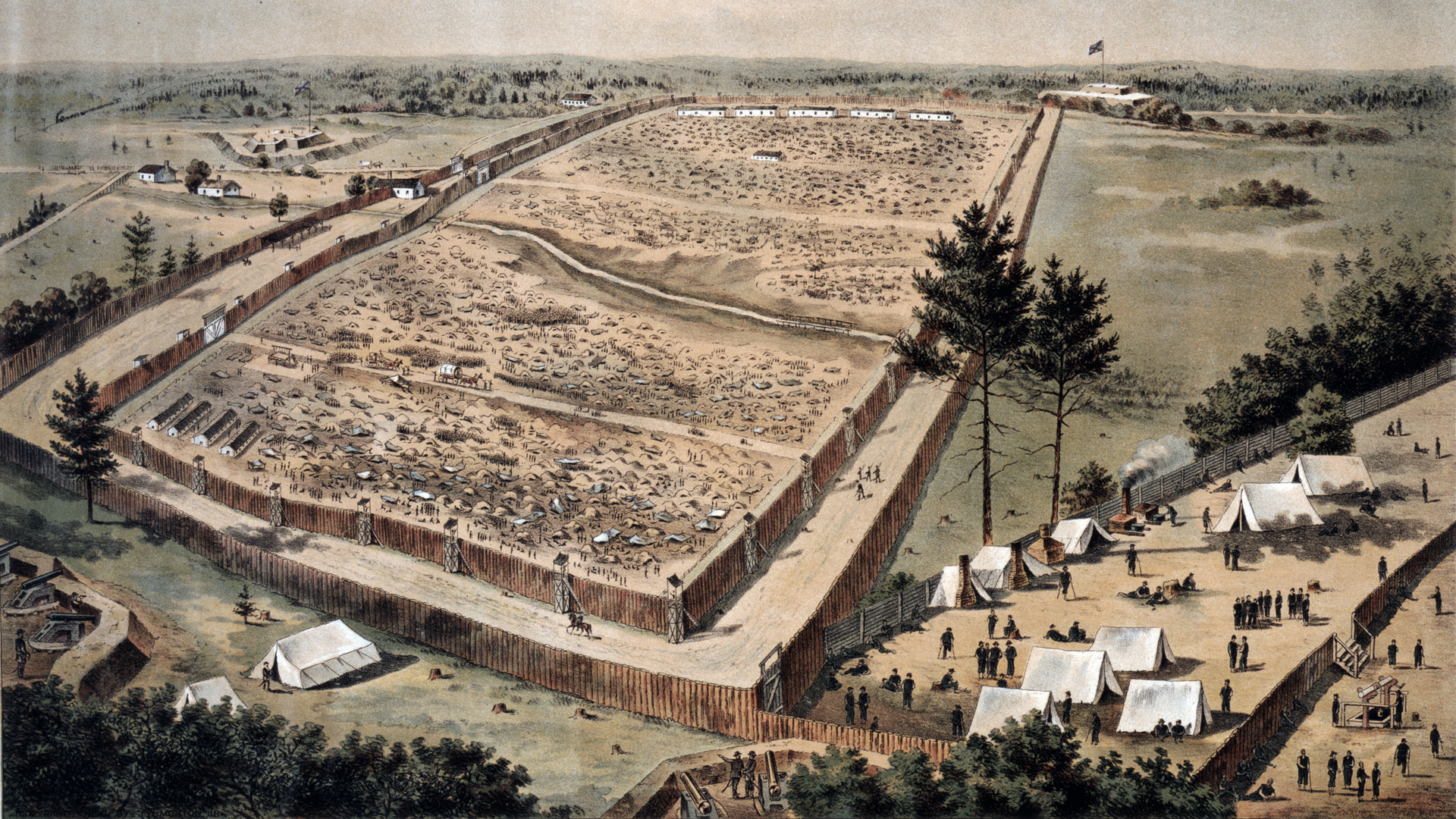

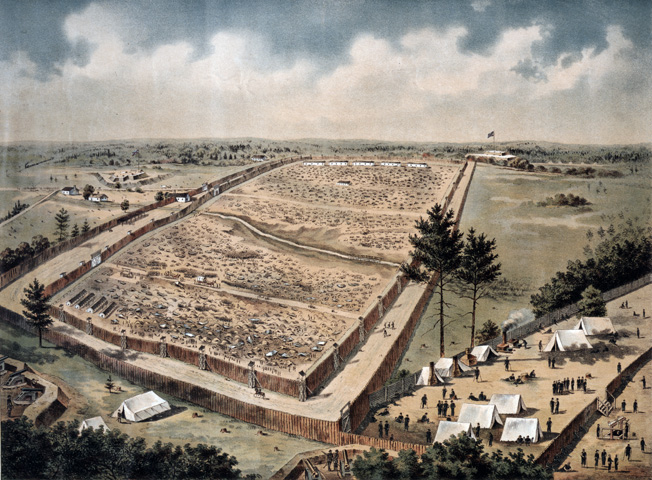

By far the most infamous of Civil War prisons, Andersonville, officially known as Camp Sumter, did not exist until the winter of 1863-1864. With defeats at Chattanooga and Atlanta in the West and expanding Union offensive operations in the East, the war was going badly for the Confederates. Union forces were penetrating ever farther into the heart of the Confederacy. It became necessary to construct a prison deep in Georgia to house increasing numbers of Union prisoners. A location near the town of Andersonville in Sumter County, approximately 60 miles southwest of Macon, was chosen because of its proximity to a rail line, a source of water from Sweetwater Creek that ran through camp, an abundance of pine trees for the construction of a stockade, and the availability of slave labor.

eye view of Georgia’s Andersonville Prison, looking northwest. The notorious fetid stream runs through the middle of the compound, with banks of cannons in the foreground and distance." width="750" height="552" />

eye view of Georgia’s Andersonville Prison, looking northwest. The notorious fetid stream runs through the middle of the compound, with banks of cannons in the foreground and distance." width="750" height="552" />

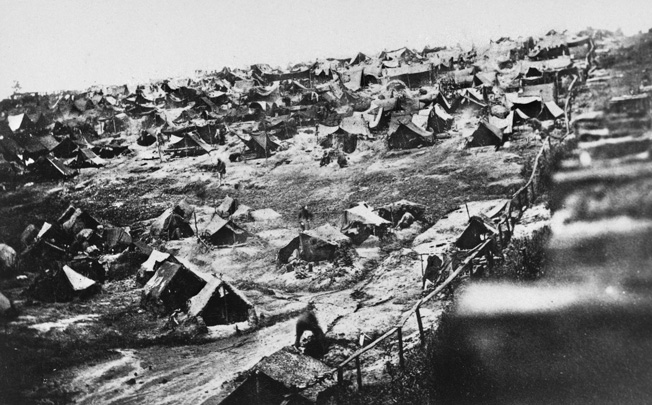

Construction began in December 1863. The original stockade occupied 16½ acres, with a pair of large gates on its western face. A fenced perimeter was set between 19 and 25 feet inside the stockade walls. This was the notorious “Dead Line,” and any prisoner crossing it would be shot immediately. On February 24, 1864, the first prisoners, 600 men transferred from Libby Prison, arrived at Andersonville. Wirz assumed command in April and was subordinate to Brig. Gen. John H. Winder, the newly appointed commissary general of Confederate prisons. The population of Andersonville swelled rapidly. In July, Wirz set the prisoners to work constructing a 10-acre expansion of the stockade. By August, starvation and disease were rampant, and the dead during that month alone totaled 2,994. The creek that ran through the compound became fetid, contributing to an epidemic-level rise in dysentery cases. Many prisoners lived in makeshift lean-to structures. Others had no shelter at all, clawing holes in the ground for whatever cover was possible. Prisoners stole from one another and fought over morsels of food. Organized gangs terrorized the camp.

Private Prescott Tracy of the 82nd New York Infantry Regiment was one of only a handful of Andersonville prisoners actually exchanged in 1864. His description of the horrors at Andersonville was later published in a propaganda pamphlet entitled Narrative of the Privations and Sufferings of United States Officers and Privates While Prisoners of War in the Hands of Rebel Authorities that circulated widely in the North. “The new-comers, on reaching this, would exclaim: ‘Is this hell?’ Yet they soon would become callous, and enter unmoved the horrible rottenness,” recounted Tracy. “The rations consisted of eight ounces of corn bread (the cob being ground with the kernel), and generally sour, two ounces of condemned pork, offensive in appearance and smell. Occasionally, about twice a week, two tablespoons of rice, and in place of the pork the same amount (two tablespoonfuls) of molasses were given us about twice a month. The clothing of the men was miserable in the extreme. Very few had shoes of any kind, not two thousand had coats and pants, and those were late comers. More than one-half were indecently exposed, and many were naked.”

From February 1864 through the end of the war, approximately 45,000 prisoners were held at Andersonville. A total of 12,913, roughly 28 percent, died and were buried in mass graves. The toll at Andersonville represents 57 percent of all Union prisoner deaths during the war. When the war ended, the focus of retribution against the South for the atrocities perpetrated in Confederate prisons would fall on Wirz, who former prisoners remembered brandishing a revolver when greeting them on arrival at the prison, shouting threats, and often losing his temper. The Northern propaganda machine had also been in motion for some time, and photographs of emaciated men, no more than living skeletons, fueled the rage against those who had encouraged, facilitated, or allowed such inhumane treatment to occur.

Born in 1823 in Zurich, Switzerland, Wirz immigrated to the United States in 1849 and opened a medical practice in Kentucky. He later moved to Louisiana with his wife and two stepdaughters. By the eve of the Civil War, his practice was prospering. With the outbreak of war, Wirz supposedly enlisted in Company A, 4th Battalion, Louisiana Volunteers, although there is little information to confirm this. He was further said to have held the rank of sergeant and fought in the Battle of Seven Pines, where he was wounded and lost much of the use of his right arm. Subsequently, he was promoted to the rank of captain for bravery on the field. Rendered unfit for further combat due to his debilitating wound, Wirz was assigned to Winder’s staff in Richmond and later detailed by President Jefferson Davis to serve as a courier to Confederate diplomats in Europe. Upon his return, Wirz was detailed by Winder to serve at prisons in Richmond, Tuscaloosa, and finally Andersonville.

Within days of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, effectively ending the war, Wirz was arrested and taken to Macon for questioning. He was briefly released and went to a nearby railroad station to return to his family at Andersonville. While waiting for the train, he was arrested again. By May 10, he was in jail in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington to await trial. Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace, later the best-selling author of the Biblically inspired novel Ben Hur, presided over the 63-day military tribunal, which lasted from August 23 to October 18.

Thirteen separate charges were leveled against Wirz, alleging such acts as Specification No. 11: “July 1, 1864, Henry Wirz did incite, and urge ferocious bloodhounds to pursue, attack, wound, and tear in pieces soldiers belonging to the U.S. Army, and a prisoner (unknown name) was so mortally wounded that on the sixth day he died.” Specification No. 4 noted: “On May 30th, Henry Wirz with a certain pistol did feloniously and with malice aforethought, inflict upon a soldier (unknown name) a mortal wound from which the soldier died.”

The remainder of the charges were similar, alleging that Wirz personally abused and murdered prisoners and ordered Confederate soldiers to do so as well. Interestingly, several of the other specifications accuse Wirz of crimes committed either before his arrival at Andersonville or during the month of August 1864, while he was actually ill and recovering at his home five miles from the prison. These allegations may have been false, or they may have been dated incorrectly. There may have been many other incidents that were never specified.

Most of the evidence against Wirz was circumstantial, and as the trial progressed, the validity of the charges hinged on the testimony of a single eyewitness, a former prisoner named Felix de la Baume, who claimed to be from France and a grandnephew of the great Marquis de Lafayette. De la Baume provided the name of one of Wirz’s victims and testified that he had personally witnessed the murders of two unnamed prisoners. De la Baume was praised for his “zealous testimony” at the trial. Before the proceedings were even completed, he was awarded a position in the U.S. Department of the Interior. However, soon after the trial, de la Baume’s true identity was discovered. His real name was Felix Oeser, and he was originally from the German province of Saxony and a deserter from the 7th New York Volunteer Infantry. Oeser supposedly admitted that he had committed perjury, but then his trail went cold. He was allowed to simply melt away.

On the night before his execution, Wirz was visited by his attorney, Louis Schade, who repeated an earlier offer from a highranking government official. In exchange for implicating Jefferson Davis, Wirz would escape the gallows with a commuted sentence. Wirz responded: “Mr. Schade, you know that I have always told you that I do not know anything about Jefferson Davis. He had no connection with me as to what was done at Andersonville. If I knew anything about him, I would not become a traitor against him or anybody else even to save my life.”

Prior to his execution, Wirz wrote two notable letters. One was to Schade, asking for help for his destitute family. The other was an appeal for clemency to President Andrew Johnson. “For six weary months I have been a prisoner; for six months my name has been in the mouth of every one; by thousands I am considered a monster of cruelty, a wretch that ought not to pollute the earth any longer,” he wrote. The appeal went unanswered.

On November 10, 1865, guarded by four companies of soldiers, Wirz was led to the gallows in the yard of the Old Capitol Prison. After ascending the stairs to the platform, the condemned man commented that he was being hanged for merely following orders. With the dome of the Capitol in the background, the hangman’s noose was placed around his neck, and the trap door was sprung at 10:32 am. Wirz’s neck did not snap with the initial drop, and he slowly strangled at the end of the rope. A crowd of about 250 spectators, each issued a ticket for admittance, watched the event with ghoulish pleasure, chanting over and over: “Wirz, remember Andersonville. Wirz, remember Andersonville.”

The debate continues to the present day over whether Wirz was justly convicted or had actually done the best he could in difficult circumstances. Initially, he was only one of several individuals who ran the risk of being charged with heinous crimes against Federal prisoners, and he was certainly a lesser target than Jefferson Davis or Secretary of War James Seddon. However, establishing a direct link between the highest echelon of the Confederate government and the sanctioning of mistreatment of Union prisoners proved a difficult proposition for prosecutors. Furthermore, placing Davis on trial might well have complicated the process of assimilating the former Confederate states back into the Union. Like the much more culpable and dishonorable Japanese emperor Hirohito following World War II, Davis went unpunished for calculated political reasons.

A lesser known figure in the prison drama was General Winder, who conveniently died of a massive heart attack on February 7, 1865. Winder was reportedly heard to brag that more Union soldiers were dying at Andersonville than the Confederate armies were killing in battle. He was also said to have turned a deaf ear to pleas from Wirz for the relief of suffering prisoners. Earlier, Winder had been responsible for the prison facilities in the Richmond area, including Libby Prison, Castle Thunder, and Belle Isle, an island in the James River where Union enlisted men were held. Had he lived, it is likely that Winder would have joined Wirz on the gallows.

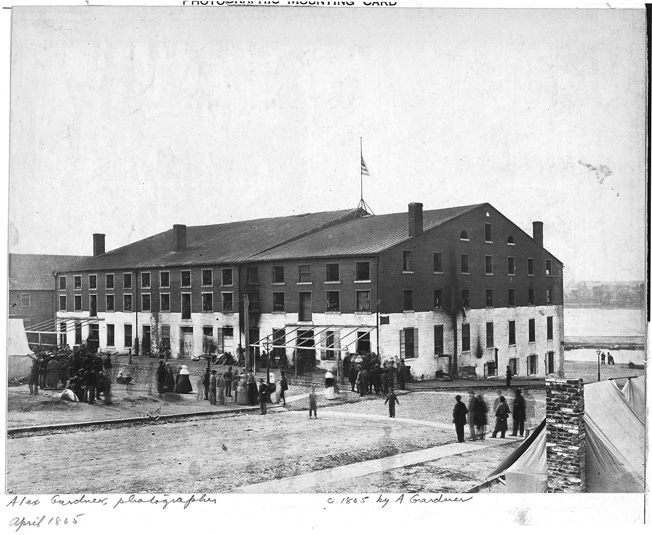

Among the other prisons located throughout the South, Libby was the most prominent. Consisting of three buildings, each four stories high, the warehouse complex was commandeered by Winder for use as a prison following the July 1861 Battle of Manassas. During the war, more than 50,000 men passed through Libby, and conditions became progressively more crowded, with no fewer than 1,200 Union officers held captive there at any given time. The windows were barred, and few of them had glass panes, exposing the prisoners to weather extremes ranging from boiling hot to freezing cold. Captives were not allowed to lie on their blankets during daylight hours and were banned from looking out the windows for fear that they might signal Union sympathizers outside

A story entitled “Horrors of Richmond Prisons” appeared in the November 28, 1863, edition of the New York Times. It noted that at Libby, “the prevailing diseases are diarrhea, dysentery and typhoid pneumonia. Of late the percentage of deaths has greatly increased, the result of causes that have been long at work—such as insufficient food, clothing and shelter, combined with that depression of spirits brought on so often by long confinement.” Describing his early days of captivity at Libby, Lt. Col. F.F. Cavada wrote: “Nothing but bread has, as yet, been issued to us, half a loaf twice a day per man. This must be washed down with James River water, drawn from a hydrant over the wash-trough. There are some filthy blankets hanging about the room; they have been used time and again by the many who preceded us; they are soiled, worn, and filled with vermin but we are recommended to help ourselves in time; if we do so with reluctance and profound disgust it is because we are now more particular than we will be in time.”

Bad as they were, Andersonville and Libby Prison were not alone in their records of deprivation. A camp at Salisbury, North Carolina, housed prisoners as early as 1861, after the Confederate government had paid $15,000 for a 16-acre tract there, including the three-story main building, six smaller brick buildings, and other structures that had once been used as a cotton mill. In the autumn of 1864, nearly 9,000 prisoners were held at Salisbury, considerably outnumbering the inhabitants of the nearby town. One prisoner referred to Salisbury as a “dark hole.” Private Benjamin Booth of the 22nd Iowa Infantry kept a daily log of deaths in the camp, noting that 58 men died on December 1, 1864, alone, and another 40 on January 12, 1865. More than 15,000 Union captives were held at Salisbury during the war, and approximately 5,000 of them died, a mortality rate of 33 percent that may have actually eclipsed that of Andersonville.

Confederate captives fared little better in Union camps. Captain Francis Marion Headley of the Confederate 8th Kentucky Mounted Infantry was captured in 1862 at Champion Hill, Mississippi, exchanged, and then captured a second time while on recruiting duty in his home state. Headley was sent to the Federal prison at Johnson’s Island, just off the coast of Lake Erie and about three miles from the city of Sandusky, Ohio. The prison opened in April 1862 and consisted of a 1.65-acre tract that included 12 two-story barracks and a hospital building enclosed by a wooden stockade with walls 15 feet high. Prisoners were allowed to receive mail and purchase food and other goods from a sutler. Some were given surplus Union uniforms to replace their worn-out clothing.

Although Johnson’s Island was intended to house only 2,500 men, the prison was regularly overcrowded and as many as 15,000 captives, most of them officers, passed through its gates during the war. The Ohio winters were harsh, and the men were subjected to sub-freezing temperatures and bitter winds that swept through their barracks off Lake Erie. Remarkably, only about 300 died. The difficult experience, however, remained with Headley for the rest of his life and contributed to his declining health.

Elsewhere in Ohio, the prisoners fared much worse. At Camp Chase, established on the outskirts of Columbus in May 1861 as a training facility for Union volunteers, 2,260 Confederate prisoners died. Three separate prisons inside the camp encompassed six acres and were intended to hold a total of 4,000 men. At its peak, the population of Camp Chase numbered from 7,000 to 10,000. Captain H.M. Lazelle, a Federal inspector who visited the camp in July 1862, noted that many of the barracks roofs leaked and that the buildings themselves were constructed so low that standing water soaked the floors for days following even moderate rain. Overcrowding, along with open latrines and cisterns, contributed to an outbreak of smallpox, and the quality of the food was so poor that the commissary officer was relieved of his post and summarily dismissed from the military.

Counting only the 2,260 noted burials and the estimated 25,000 Confederate prisoners who transited Camp Chase during its operation as a prison from the summer of 1861 through the end of the war, the mortality rate at the facility may be estimated at just under 10 percent. Camp Douglas, the most infamous of Northern prisons, opened in Chicago in 1861 as a training camp for volunteer infantry units and was permanently designated a prison camp in January 1863. At times, both Confederate prisoners and Union parolees were held there together.

During the war, more than 26,000 Confederates were imprisoned at Camp Douglas at various times, and the estimated number of deaths ranged from 4,500 to more than 6,000. Controversy surrounds the final mortality rate due to the allegation that a large number of prisoner deaths were never recorded, the bodies either buried in unmarked mass graves or simply considered unaccounted for. On the other hand, it was charged that an unscrupulous contractor simply buried a number of empty caskets to increase his payment from the U.S. government. Regardless, the generally accepted mortality rate at Camp Douglas is 17 to 23 percent.

Constructed on land previously owned by U.S. senator Stephen Douglas (hence the name), the camp was in a low-lying area where drainage was inadequate. Conditions deteriorated to such an extent that Henry W. Bellows of the U.S. Sanitary Commission wrote to Maj. Gen. William Hoffman, commissary general of prisons: “Sir, the amount of standing water, unpoliced grounds, of foul sinks, of unventilated and crowded barracks, of general disorder, of soil reeking miasmatic accretions, of rotten bones and emptying of camp kettles, is enough to drive a sanitarium to despair. I hope that no thought will be entertained of mending matters. The absolute abandonment of the spot seems to be the only judicious course. I do not believe that any amount of drainage would purge the soil loaded with accumulated filth or those barracks fetid with two stories of vermin and animal exhalations. Nothing but fire can cleanse them.”

Depending on the sources consulted, the population of Camp Douglas peaked at anywhere from 9,000 to 12,000, fell sharply later in 1862 following an exchange under the Dix-Hill Cartel, and then rose significantly by mid-1863. During the winter of 1862-1863, more than 200 prisoners were crowded into barracks measuring no more than 20 by 70 feet. Prisoners were required to stand in ranks in ankle-deep snow and ice. Temperatures dipped below zero, and up to 1,700 died during that winter alone.

A number of Illinois Militia and U.S. Army officers were in command at Camp Douglas. One of the more memorable was Colonel Charles V. DeLand, previously the commander of the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters. DeLand took charge of the camp on August 18, 1863, and attempted to tighten discipline by putting the prisoners to work on an improved stockade. More than 70 escapes were attempted at Camp Douglas, and while DeLand was in command more than 150 prisoners, 26 in a single incident, broke out. DeLand was known for the severe punishment he dispensed, once having prisoners of the 8th Kentucky Cavalry remain standing at attention for a lengthy period after a tunnel was discovered under their barracks and ordering guards to shoot any of the prisoners who sat down. One was killed and two were wounded. On another occasion, three men were hung by their thumbs for an hour with their toes barely touching the ground because they allegedly threatened another prisoner who had been an informer.

As the war progressed, the Union armies took prisoners in ever-growing numbers. Of the 12,000 Confederates that inhabited the prison at Rock Island, Illinois, during the war, 2,000 died. At Point Lookout, Maryland, 50,000 prisoners passed through during the war and from 12,000 to 20,000 were housed there at any given time. Among these, an estimated 4,000 deaths occurred, for a rate of roughly eight percent. The famous Southern poet Sidney Lanier was a captive at Point Lookout and contracted tuberculosis there that dramatically shortened his life. He died at age 39.

At Fort Delaware, on Pea Patch Island in New Castle County, Delaware, the population swelled to more than 13,000 prisoners following the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863 and increased to more than 30,000 by the end of the war. The prisoners suffered about 2,500 deaths. One prisoner from Georgia was starved from a healthy weight of 140 pounds to 80, while another prisoner wrote graphically, “The bacon was rusty and slimy, the soup was slop filled with white worms a half-inch long.”

In the spring of 1864, the problem of overcrowding had become so severe that a new prison was constructed on the site of a former mustering location for Union troops at Elmira, near the banks of the Chemoung River in upstate New York. Troops were detailed to convert the dilapidated camp into a prison and build a stockade. By July, 700 prisoners had been transferred from Point Lookout, and a month later the prison population swelled to more than 10,000 Confederate enlisted men. Conditions at Elmira were terrible from the beginning. The prison was below the level of the river, making drainage problematic. The barracks could hold only about half the prisoners; the rest were forced to live in tents. With the onset of winter, the men were exposed to extreme cold. Disease was widespread. By war’s end, more than 12,000 prisoners had occupied Elmira, known to many of them as “Hellmira.” Nearly 3,000 died, yielding a harvest of death approaching 25 percent and rivaling that of Andersonville.

On November 1, 1864, Dr. Eugene Sanger, the commander and camp surgeon at Elmira, wrote to U.S. Army Surgeon General Joseph Barnes: “Since August there have been 2,011 patients admitted to the hospital and 775 deaths. Have averaged daily 451 in hospital and 601 in quarters, an aggregate of 1,052 per day sick. At this rate the entire command will be admitted to hospital in less than a year and thirty-six percent die.” Elmira operated for 15 months, and on July 1, 1865, nearly three months after Lee’s surrender, 218 Confederates remained in the facility’s hospital. The last prisoner departed Elmira on September 27.

Union Commissary General Hoffman has been both praised and vilified for his administration of the Union prisons during the Civil War. A career officer, he had been a classmate of Lee’s at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He was a veteran of the Indian wars and the Mexican War. Captured in Texas at the beginning of the Civil War, he was exchanged on August 27, 1862. As commissary general, he was subordinate to Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs, who instructed him that the barracks at the Rock Island prison should be “put up in the roughest and cheapest manner, mere shanties, with no fine work about them.” Meigs, who had lost a son in the war, had no sympathy to spare on Confederate prisoners.

While adequate supplies of food and clothing were available most of the time, some civilian contractors took government funds and either failed to deliver goods or dealt in such shoddy products that clothing and blankets were of such inferior quality as to be of little use. Likewise, contracted meat was delivered to prisoners already spoiled and unfit to eat. At Point Lookout, Major Allen G. Brady, the prison provost, was widely believed to have taken provisions meant for prisoners and kept them for himself.

Hoffman’s frugality became legendary. Although Congress had appropriated adequate funds for the purpose of caring for prisoners, he was reluctant to make such purchases and actually returned $2 million to the Treasury at war’s end. He once ordered a prison commander, “As long as a prisoner has clothing upon him, however much torn, you must issue nothing to him.” When a Confederate officer questioned Hoffman about his ill treatment at Camp Chase, the commissary general bluntly stated that it was “retaliation for innumerable outrages which have been committed on our people.” After the war, Hoffman was officially commended for his “faithful, meritorious, and distinguished services as Commissary-General during the Rebellion.” He retired from the army in 1870 with his permanent rank of colonel and died at the age of 77 in 1884.

An 1864 report by the U.S. Sanitary Commission accused the Confederates of a predetermined plan to mistreat Union prisoners. No doubt this charge, unproven then or now, influenced the desire for retribution against Rebel authorities who supposedly had perpetrated such an outrage. The debate continues to rage among historians to this day. At the very least, it appears that the Federal government endorsed a policy of retaliation for the poor treatment of Union prisoners in Confederate hands. Secretary of War Stanton went on record, writing to Hoffman: “The Secretary of War is not disposed, in view of the treatment our prisoners are receiving, to erect fine establishments for their prisoners.” That the North, largely untouched by the war, was much better able to care humanely for its prisoners than the starving South, is beyond dispute. Whether it cared to do so remains an open question—at least in the minds of pro-Union historians.

In the end, Henry Wirz, the only individual on either side to be punished for inhumane treatment of prisoners, remains the most controversial figure of the Civil War’s tragic prison legacy. One historical footnote remains. The defense that he had only followed orders failed to absolve Wirz of guilt in the mind of the court and established a precedent for the trials, 80 years later, of Nazi war criminals who made the same claim at Nuremberg following World War II. Simply acting on orders, it was judged, does not relieve an individual of his larger responsibility to humanity. It is a distinction that remains, in the wake of the 9/11 attacks and the government’s concomitant response to terrorism, very much in question today.

You must be logged in to post a comment.